blog: How bicycle infrastructure can enable inclusive access

Tuesday 17th October 2017

The way many people think about disability continues to negatively impact on how we design our cities. People with physical limitations such as mobility impairments are often disadvantaged and excluded due to the way built environments are designed. However, building bicycle paths and related infrastructure can help to unlock access to the city for those who use wheelchairs or mobility scooters, facilitating more inclusive mobility for all.

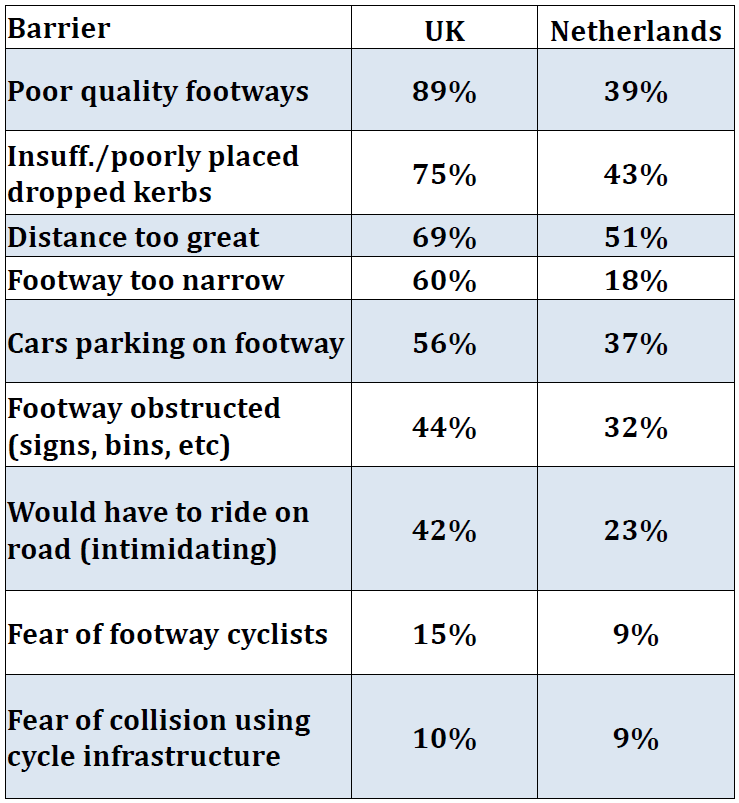

Wheelchair and mobility scooter users face more challenges than most when it comes to moving about a city. Some commonly encountered barriers include a lack of dropped kerbs, people parking on the footpath, and the surface of the footpath being bumpy and broken. The presence of signposts, bins, advertising boards and pedestrian overcrowding can also hinder progress.

To find out more I carried out a questionnaire with over 200 wheelchair and mobility scooter users in the UK, Netherlands, and Canada. The UK consistently received the worst ratings for footpath quality and obstructions. The opposite was true for the Netherlands.

So, why is there such a difference between the UK and the Netherlands for wheelchair and mobility scooter users? One reason appears to be that users these mobility aids are able to move about towns and cities in the Netherlands more easily due the presence of bicycle infrastructure. Bike paths, lanes, and cycle-friendly junctions are widely found in the Netherlands across city centres, small towns, rural villages and intercity routes. Just as hard to miss when in the Netherlands is the large number of mobility scooters, wheelchairs, and specially-adapted bicycles making use of the bicycle infrastructure.

To check if the benefits were real rather than a figment of my imagination, Dutch users of these mobility devices were asked how often they use bicycle infrastructure, and the results were clear. The majority stated that at least half of their journeys involved the use of bicycle infrastructure, while only about 10% indicated they had never used it.

Respondents in all three countries were asked if they preferred using bicycle infrastructure over footpaths; again, I found that most preferred using the bike paths, with only a few saying that they offered a worse experience.

It seems clear that for many journeys, bicycle infrastructure can offer an ideal form of infrastructure for users of wheelchairs and mobility scooters. Being designed for wheeled devices, they feature fewer of the obstacles commonly found along footpaths designed with able-bodied pedestrians in mind.

So, bicycle infrastructure can help to achieve “access for all”, a key principle of universal design, but its use by wheelchairs and scooters also introduces scope for conflicts with faster moving cyclists. Anecdotal evidence from my Master's study found that respondents in the Netherlands reported conflicts with cyclists less frequently than in the UK and Canada. Possible reasons included the greater width of Dutch cycle lanes and the slower average speeds associated with higher levels of utility cycle trips, when compared with those in the UK and Canada.

These findings, and further research in this topic area, could inform inclusive design considerations for cycle lanes in the UK at a time when significant urban and inter-urban investments are being funded. If you would like to know more about this research you can download the paper here, or contact one of the ITP team on the 'get in touch' page.